Last week I lectured on Horace to students reading in translation. I think it was Robert Frost who defined poetry as “what gets lost in translation,” but with some poets it seems to be more problematic than with others, and Horace is notoriously difficult to translate. For example, I commented that I didn’t like it where the translation we were using gave “hugging” to convey the force of “urget” in Odes 1.5 (the one addressed to Pyrrha: a whole book of translations of this one poem was collected by Ronald Storrs). You hug your mother… whatever Pyrrha and her youthful admirer are doing is a bit different. In order to convey something of the difference between translations of the same poem, I also gave the students the translation by Milton, where he tries to render the poem “almost word for word without Rhyme according to the Latin Measure, as near as the language will permit.”

I was very much presenting this to the students as a problem: what you lose by not getting the Real Deal, i.e. the text in its original language. But perhaps – especially since I had also been talking about Catullus 51, a “translation” of Sappho into Latin – I ought also to have spoken about translation in a more positive light, not just as a problem but as a fascinating cultural and linguistic process.

It’s in that light that I present two different Scottish translations. Glasgow poet Tom Leonard gives a Glaswegian version of this famous poem by William Carlos Williams:

.

This is Just to Say

.

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

.

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast.

.

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold.

.

Here is Leonard’s take. I have a copy of this stuck on the front of my frij… I mean, fridge.

.

Jist ti Let Yi No

.

from the American of Carlos Williams

.

ahv drank

thi speshlz

that wurrin

thi frij

.

n thit

yiwurr probbli

hodn back

furthi pahrti

.

awright

they wur great

thaht stroang

thaht cawld

.

If you look at it for a bit, I find that the words which start to stick out are the ones which are retaining phonetically under-determined aspects of their “proper” spellings: awright, great.

This one was an old favourite of mine. Only a couple of weeks ago, however, I got hold of a copy of a book I had long known about but hadn’t previously looked at. This is the translation of the New Testament into Scots which was made by W.L. Lorimer, who was Professor of Greek at St Andrews. Lorimer left his translation complete when he died in 1967, and it was edited by his son.

I don’t find this easy to read (of course, one of the reasons why, despite the efforts of poets such as MacDiarmid, Scots is not a standard literary language is that there had not previously been a translation of scripture into Scots: Scots have always consumed the word of God in Latin or “English English”), and the book does not include a glossary. (Although I was born and brought up in Glasgow, and call myself a Scot, I think my spoken English sounds effectively like that of a southern Englishman; but many Scots who sound like Scots would find some of this quite hard as well).

But some of it seems tremendous. Here I’ve selected a bit where you can see how Lorimer translates a quotation from Isaiah, and how well he conveys John’s vehemence of speech:

John the Baptist (Luke 3)

… an he came forrit an towred the haill o Jordanside, preachin a baptism o repentance for the forgieness o sins – een as it is written i the Prophecies o Isaiah:

A cry sae loud i the muirs:

‘Redd ye the gate o the Lord,

mak ye straucht his pads!’

Ilka gill an cleuch sal be made queem,

an ilka knock an knowe become a laich;

the wimpelt gates sal be strauchtit,

an the roch roads made sound;

an aa livin will see

the saufin wark o God!

Tae the thrangs o fowk at cam out seekin baptism at his haund John said, “Getts o ethers, wha warnished ye tae flee frae the comin wraith? First lat me see your repentance kythe in your lives! An dinna ye sae muckle as think o sayin til yoursels, ‘We hae Abraham for our faither’: I tell ye, God could raise up childer til Abraham out o thir stanes. The aix is lyin else at the ruit o the trees, an ilka tree at beirsna guid frute will be cuttit doun an cuissen intil the fire.”

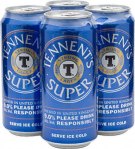

Understanding what’s going on in the Leonard poem seems to require that we acknowledge and recognise the model. We need to remember the earlier poem, and make the contrast between its “correct” language, marked as “American” only (as it seems to me) in the use of the word “icebox,” and Leonard’s phonetically rendered Glaswegian. From the point of view of Leonard’s speaker (writer?), Williams’ language, which might have been called unmarked and everyday by somebody else, is foreign and speaks across a gap of translation. The poem represents not only an assertive (perhaps even aggressive) claim for the Glaswegian’s language, but also a claim that the experience of the Glaswegian drinker of extra-strong lager has upon our attention as much as that of the plum-eater (who is no more a generalised everyman than the Glaswegian is).

One wouldn’t expect, however, to find Lorimer competing in this kind of way with the writers of the Greek of the New Testament, and the introductory material by his son paints a picture of a careful scholar of Greek and of Scots who was also a pious Christian. But questions of language politics are clearly visible from Lorimer as well. The following does not come from the main text of his translation, but was a jeu d’esprit which his son put into the book as an appendix.

The Temptation of Jesus (Matthew 4)

Whan he hed taen nae mait for fortie days an fortie nichts an wis fell hungrisome, the Temper cam til him an said, “If you are the Son of God, tell these stones to turn into loaves.”

Jesus answert, “It says i the Buik:

Man sanna live on breid alane,

but on ilka wurd at comes

furth o God’s mouth.”

Neist the Deil tuik him awa til the Halie Citie an set him on a ledgit o the Temple an said til him, “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down to the ground. For it says in the Bible:

He shall give his angels charge concerning thee,

and in their hands they shall bear thee up,

lest at any time thou dash thy foot against a stone.”

Jesus answert, “Ithergates it says i the Buik: ‘Thou sanna pit the Lord thy God tae the pruif’.”

So there we have it: Jesus spoke Scots, but the Devil spoke Authorised Version English. (It reminds me of the practice of giving sinister or effete characters English accents in Hollywood movies.)

I was quite shocked…

Great stuff!

Hi Richard – just thought I would drop by and wish you well with your new blog site!

All the best,

Tony Francis

Hello Tony: thank you very much!

All best,

Richard